The Origin Story

December 4, 2018

Out of the Mystic

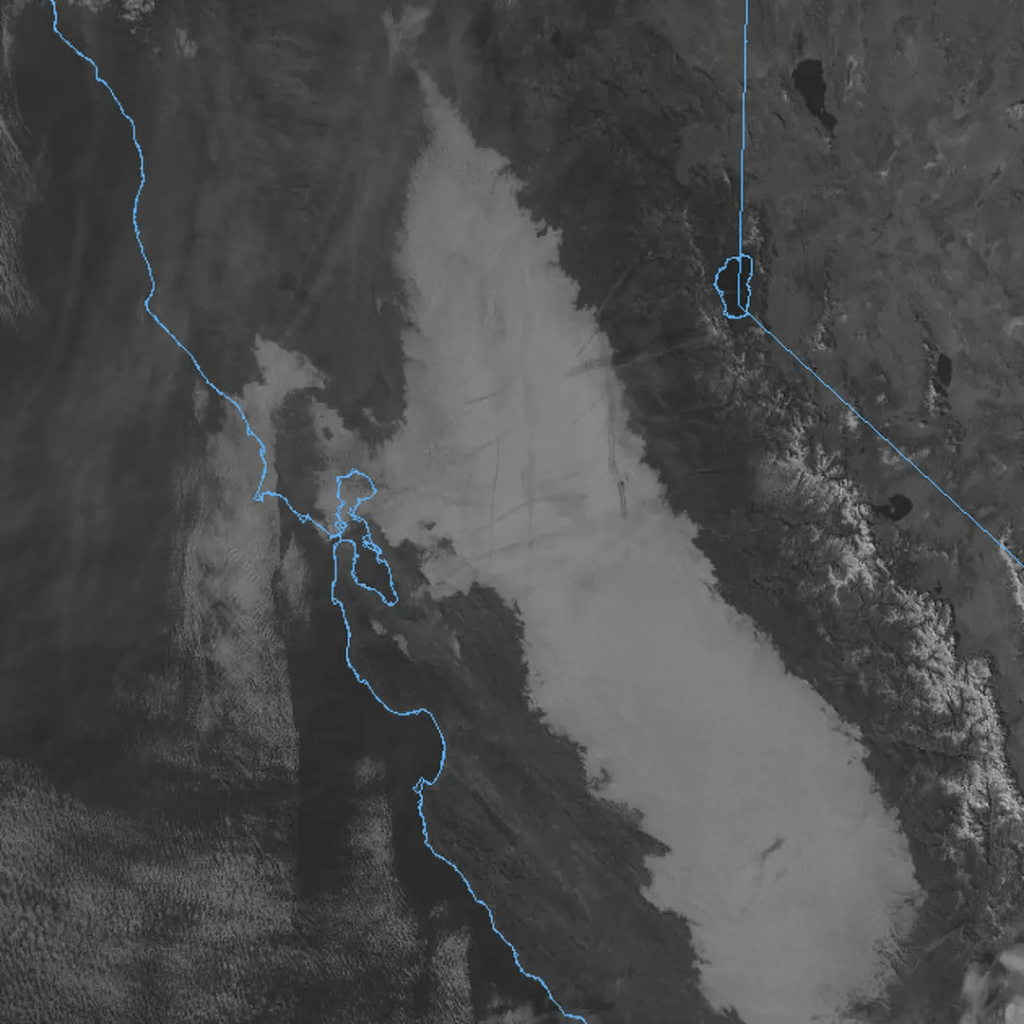

December 4, 2018… A cold, nearly winter, overcast Tuesday morning. Bicycle rides on Tuesdays are routinely on roads less traveled east of my home in Merced. On this day, there were three of us, Pete, Tom, and yours truly, on the saddles. It’s apparently different from when on horseback you’re in the saddle that’s on the horse’s back.

We were just making our way past the last of the pistachio orchards approaching the rangeland of the Sierra foothills when a little blue heeler spotted us, popped out of the rows of trees, and ran up to greet us.

There’s no other way to explain my reaction other than it was love at first lick. My second thought was I’m taking this dog home. I’ve always had the notion of adding to the long list of Labrador Retrievers canine family members we’ve kept over the past 32 years, either a Standard Poodle or an ACD, Australian Cattle Dog.

The Dilemma

Why a Standard Poodle? That’s easy, because of Charley, John Steinbeck’s Standard Poodle there for companionship and comic relief, was along for his journey in Travels with Charley.

Though I was only six when Travels was published—I read it later in college—the book touches on themes of nostalgia, identity, and the complexities of post WWII America. I vividly remember how Charley was more than a pet along for the ride. He was an essential character in Steinbeck’s assessment of the rapid change he witnessed taking place in post war America.

Homeward Bound

Why an ACD? Because Bluey, who lived to 29, holds the Guinness World Record as the “Oldest (verified) Dog to have Ever Lived”. Since longevity is a characteristic of ACD’s, and Skidboot’s intelligence declared him the “World’s Smartest Dog,” Heelers are the very embodiments of hearty stock with brains. Labs are friendly and playful, Poodles smart and sophisticated, but they live on average for 12 years. Note: neither ever earned titles of longevity and intelligence.

Of course, I would end up doing due diligence, stopping by the few residences along South Bear Creek and asking if they knew to whom this little blue heeler, perhaps less than a year old, belonged. I would then place ads in the local newspaper and list her on social media as lost. And I would contact the local county animal shelter and SPCA about her status and advice on the statute of limitations for claiming a “found” lost dog.

But honestly, the little blue heeler wasn’t lost. She found me and I was prepared to suffer the two weeks that is required before you can claim “ownership” of an abandoned animal. I can’t explain the anxiety I experienced in those two weeks… It bordered on heartbreak akin to that I felt longingly for Molly and Godiva, our yellow and chocolate Labs lost to old age and knowing that dogs only occupy the physical world for a short time but live on in our hearts and memories. The longer they live, the greater the memories.

On the ride home with SoBe, reluctantly tethered to my side by a leash fashioned from roadside rope, she must have been wondering, “what’s with this thing around my neck?” She couldn’t imagine how her life was about to change. I don’t know what perils she faced before I found her so it wasn’t hard to accept her pulling against the rope while I struggled to stay upright. I knew it was this little ACD’s fate to securely join Luna and Dakota, another pure bred English yellow and black Lab rescue respectively, that would erase any of her anxiety and add to the joy of yet another member of our pack. We own a Subaru. We’re dog people.

At the corner of Plainsburg Rd and E. South Bear Creek, as I looked at the signpost marking the intersection, a perfect name appeared to me. SoBe, from South Bear Creek. No, I did not name my dog for an iced-tea beverage from South Beach. I decided to call my wife to ensure safely bringing SoBe home as the traffic increases from this point to home.

The phone call went something like this:

“Hey sweetie, you’ll never know what I encountered on this morning’s bike ride,” “A damsel in distress…” I intoned.

“Oh, and so what is it that you needed to call me about your encounter?” my skeptical wife replied.

Thinking fast, I thought, “Well, I’m smitten with finding this pup’s home and since I’m getting closer to traffic, I thought you might be able to come fetch us in the Outback, you know, the dog friendly Subaru.”

I was amazed and somewhat shocked when my wife, after sighing, agreed to leave her work to meet us at SoBe’s namesake intersection. I knew she would resist my intent to keep SoBe. She’s skeptical of my “great ideas” about 85% of the time. So, I assured her that something this beautiful and sweet had to belong to someone. Only later I lamented the fact that SoBe was deliberately abandoned and she deserved so much more in life. I leveraged keeping her on that basis. My wife eventually relented. SoBe reigned in that 15% of good ideas!

Welcome to your forever home Now, just make it through the next two weeks…

The Interloper

While sitting out the two week statute of limitations, we had SoBe vaccinated and spayed. With no response to two weeks of searching for her “owner” due diligence, we formally adopted SoBe, registering her with the county, getting vaccination tags and a name tag with our address and phone number.

As spirited and fearless as a heeler can by way of breeding be, SoBe quickly adapted to adoption and membership in our pack. Luna was the senior member but not the alpha. She was a goofy love bug. Dakota was a few years younger, arriving at our home a few years after Luna. She was a tad less jovial, nevertheless asserting herself alpha-like. This perhaps because as a rescued mix of German Shepherd and Labrador Retriever she may have been a little less “refined,” more given to instinct.

SoBe, bred to nip at the heels of animals a thousand times her mass, had chosen to be an unofficial “alpha,” age and/or instinct be damned, much to Dakota’s chagrin. There was always tension simmering between the two of them that might erupt as play would escalate to combat, not unlike that of the sibling rivalry between our two boys. Luna simply dismissed all of the dramatic posturing, finding Swiss-like neutrality leaving any quarreling to the late-comers.

A Dog Is (for) Life

It is as though I find myself in the same circumstance as Steinbeck in my own Sisyphus and Associates musings and screeds navigating encounters and insights, nostalgia and identity in contemporary America on my two-wheeled travels. Having SoBe long for me as I long for her when we are apart, has given me a portal to gratitude that the evening news, now 24-7, robs from me. I have found out there, on the road, traveling through the West such generosity, encouragement, and genuine curiosity. I have a sense that the America in the news or online, isn’t necessarily the America most of us know. I just know that trust is earned when it comes to people. When it comes to dogs, it’s just a lot easier to build. Now, how to acquire a side car to bring SoBe along for the ride…

Time Flies Like an Arrow

Since those early days introducing SoBe to our pack, we’ve lost Luna and Dakota. Well, sort of. Their ashes, along with Godiva’s are in our closet awaiting a fitting internment. Molly’s ashes are entombed in a boulder at the top of Chair 3 at Dodge Ridge where she spent her best years.

My intent is to continue sharing SoBe stories. SoBe is still with me, which means there’s more road to travel. This isn’t just about finding SoBe; it’s about what she replaced, what she has filled, what she represents in the ongoing cycle of love and loss that comes with keeping dogs. With all due respect to all of my family and friends, SoBe is my best friend.

12/8/25 Sisyphusdw7.com

In memory of Buddy, Bill and Ginger’s baby…