A Public Service Message (Warning: Graphic photos follow)

I greeted the good doctor early on a recent November morning, “You know Dr. Mehrany I have a low incentive threshold,”

“How’s that Mr. Jones?” he asked.

“Well, all it takes is a maple bar in your waiting room, and I’m willing to have you take a knife to my face.”

“I guess it beats cancer, eh?” he replied.

“But what about donut-induced heart disease or diabetes?” I beseeched.

“Everything gives you cancer, there’s no cure, there’s no answer except that Mohs surgeries are 98-99% successful, the most efficacious treatment for any cancer,” retorted the doctor, “You take your chances with cholesterol and blood glucose.”

Drop the mic!

My apologies to Dr. Mehrany whose response I doctored and Joe Jackson’s line about cancer from Everything Gives You Cancer.

What are the Odds?

And so began my most recent appointment with Kosgrow Mark Mehrany, MD, a skin cancer specialist whose practice is divided between San Jose and Modesto, near my home in the Central Valley. This would be my fourth basal cell carcinoma removal by way of a procedure known as a Mohs surgery.

Skin cancer is the most common type of cancer in the United States, with about 1 in 5 people developing it at some point in their lives. Each year, more than 3.5 million cases are diagnosed, making it a significant health concern. As one of the 3.5 million—it’s not a league in which I am proudly enrolled.

It Pays to Have Good Doctors

My now deceased family doctor, Christian Gallery, began detecting suspicious growths he diagnosed as a type of pre-cancer called actinic keratoses a decade ago. He was comfortable removing most of these scaly patches on my back and chest by freezing or a simple surgical removal, the standard treatments. When he suspected there may be a more serious basal cell carcinoma on my face he recommended I see a specialist.

That was my first encounter with Dr. Mehrany in his office in Modesto, CA in the spring of 2019. Dr. Mehrany confirmed Dr. Gallery’s diagnosis by biopsying a spot on my cheek. The resulting confirmation was that of a basal cell carcinoma he proposed to remove, using what is known as a Mohs micrographic surgery.

Mohs surgery is a procedure performed by a specially trained surgeon. Dr. Mehrany’s six page curriculum vitae* is impressive, but the fact that in his career he has performed over 20,000 Mohs surgeries is even more reassuring.

His manner is straightforward yet he has an amicable sense of humor. At least he feigns to laugh at my jokes. And once he’s executing the procedure his focus and attention is razor-sharp. Ugh. His staff are all equally genial and give you the sense that even though the office waiting room is full, each patient is accorded sincere regard and every effort is made to erase apprehension. Perhaps that’s the purpose of the donuts and coffee…

What Is Dr. Mehrany Screening For?

Skin cancer comes in a variety of forms, and some kinds are more frequent or dangerous than others. More than 98% of skin cancers are either basal cell and squamous cell carcinomas. Melanoma is another, less common type of skin cancer. Melanoma can be deadly unless it’s detected and treated early. Getting your skin checked regularly by a skin cancer specialist, like Dr. Mehrany, helps to protect you by catching skin cancer early when it’s easiest to cure.

Given that my youth into adulthood was spent when skin cancer detection wasn’t as refined as it is today, all of the summers spent in swimming pools, backpacking in the Sierra, riding bicycles, running, sailing, golf, and skiing meant I had a healthy year-round exposure to UV wavelengths of natural sunlight. Skin cancer develops when skin cells grow uncontrollably, in my case due to damage from ultraviolet (UV) rays from the sun, or tanning beds for those whose desire for sun-kissed aesthetics don’t have the time or hobbies to bronze in hours of exposure outdoors. And for those whose labor exposes them to harmful solar radiation, my sincere empathy.

This damage can lead to changes in the DNA of skin cells, resulting in abnormal growths that can become cancerous. Though I became aware of damage that repeated long exposure to sunlight was a form of Russian roulette that only emerged later in life, my haphazard mitigation with protective clothing and topical sun screens was preempted by naiveté. In the hypocrisy of pretending that tanning beds were for the vain, I was convinced that celebrating life in the great outdoors could achieve the same aesthetic that was beyond consequence. Vanity, it appears, is in the skin of the beholder.

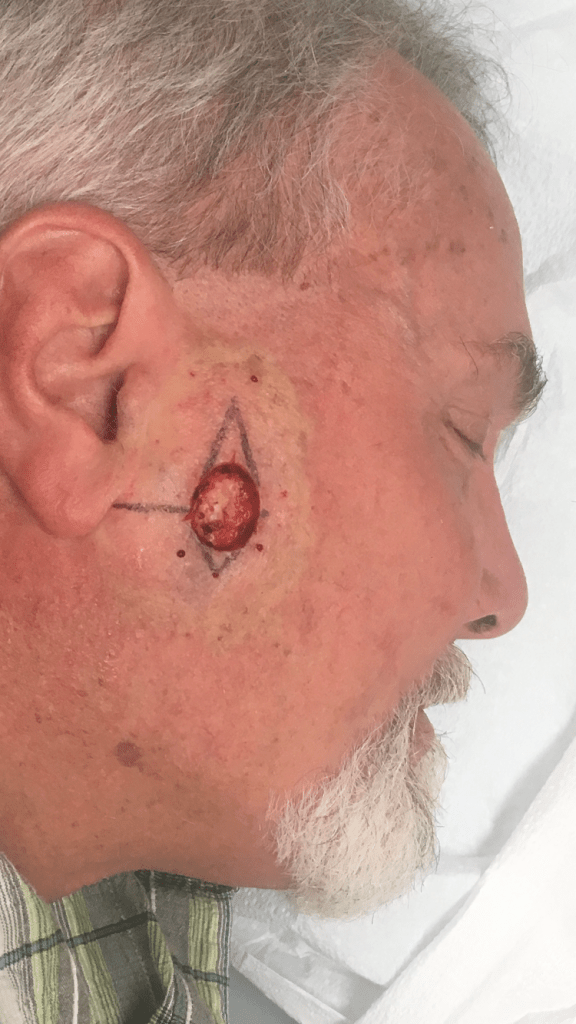

Warning, the photos below are quite graphic. You can thank my wife who enjoyed the surgeries from the peanut gallery.

April 2019-The First Round: Mapping the sutures

Cheek surgery site with stitches and the surgical wound dressing you flaunt leaving his office

January 2021-Round Two: Can’t You Hear Me Noggin

Start to finish, about three weeks. “Covid doesn’t stop for cancer…” declared Dr. Mehrany (I neglected to “flip” the selfies)

February 2022-Round Three: Another Cheek Crater

in the middle photo is the pressure dressing, awaiting results of the first scraping. We were still masking.

November 2025-Round Four: Too Close to the Eye for Comfort

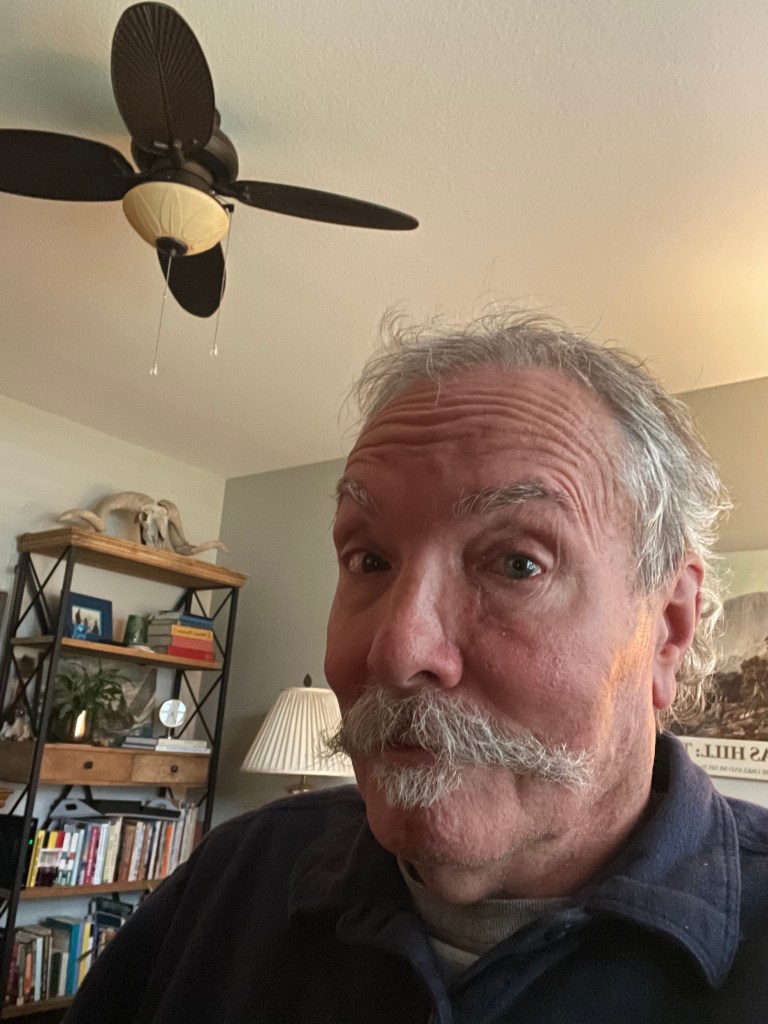

Oddly, all four carcinomas have clustered on the right side of my face. (The flipped selfie makes the appearance of the scar on the left side. I assure you, it’s on the right side.)

How Mohs Surgery Actually Works

Armed with a pocket full of syringes, donning appropriate PPE and surgical loupes, with a surgical blade called a curette, and a cauterizing pen at hand, Dr. Mehrany removes a layer of cells. Although the official name for the procedure is Mohs micrographic surgery, the shortened version of Mohs Surgery is common.

The surgery is performed as follows: the skin suspicious for cancer is treated with a local anesthetic, so there is no feeling of pain in the area. In fact, the most painful part of the procedure is the “poke and burn” of the injection. To remove most of the visible skin cancer, the tumor is scraped using a sharp instrument called a curette. A thin piece of tissue is then removed surgically around the scraped skin and carefully divided into pieces that will fit on a microscope slide; the edges are marked with colored dyes; a diagram of the tissue removed is made; and the tissue is frozen by Dr. Mehrany’s technician, Manny. Thin slices can then be made from the frozen tissue and examined by the doctor under the microscope.

I asked Dr. Mehrany if there’s any way to know when the damage actually happens. Turns out it’s impossible to pinpoint. The two biggest variables are how aggressive the mutation is and how well your immune system fights back. The damage could have occurred decades ago, but when it decides to show up as cancer? That’s anyone’s guess.

Of course minimizing exposure is the gold standard for preventing skin cancers, however a history of sunburns along with genetic factors of having lighter skin and a family history of skin cancer are the most common causes. Other factors include having many moles or atypical moles and certain skin conditions. When the damage occurs and how long it takes for the cells to mutate is widely variable. Thus any pale skin entitlements are moot when it comes to skin cancer.

It Doesn’t Smell Like Bacon Frying in the Kitchen

Most bleeding during the procedure is controlled using light cautery, although occasionally, a small blood vessel is encountered, which must be tied off with suture. A pressure dressing is then applied, and you’re asked to wait while the slides are being processed. Dr. Mehrany will then examine the slides under the microscope to determine if any cancer is still present and subsequently annotate his map of the cancer location accordingly.

If cancer cells remain, they can then be located at the surgical site on the patient by referring to the map. Another layer of tissue is then removed, and the procedure is repeated until Dr. Mehrany is satisfied that the entire base and sides of the wound have no cancer cells remaining. As well as ensuring total removal of cancer, this process preserves as much normal, healthy surrounding skin as possible.

More Donuts Await

The removal and processing of each layer of tissue take approximately 1-3 hours. Only 20 to 30 minutes of that is spent in the actual surgical procedure. The remaining time is required for slide preparation and interpretation. It usually takes the removal of two or three layers of tissue (also called stages) to complete the surgery. Fortunately for me, the most recent surgery took only the removal of a single layer of tissue. Even the more severe first case only took two tissue layers. I figure that’s about a donut per stage

Therefore, by beginning early in the morning, Mohs surgery is typically finished in one day. I was in at 7:30 am and out by noon. At the end of Mohs surgery, you will be left with a surgical wound free of tumor which is then reconstructed that same day. Several options for reconstruction may be discussed with you in order to weigh your preference of what will provide the best possible cosmetic outcome versus what will provide the easiest and simplest recovery.

Time to Lace Up the Pigskin

Suturing the wound was interesting from my perspective. The site was completely numb, so I did not feel pain. However, the snugging of the suture was a little unnerving. For this surgery, there were some 25 stitches. Times four surgeries—those are the battle scars of freedom. Or inattention. Dr. Mehrany’s skill at reconstructing the surgical wound is truly his genius.

There was modest discomfort following the wearing off of the anesthetic. Not unlike what you might feel after a dental procedure like a filling or crown, and the slight pain was softened by a couple of extra strength Tylenols. Sorry RFK, I’ll risk autism for relief from surgery whether I plan to get pregnant or not.

Moving Forward

These days wide full brimmed hats have replaced ball caps. UV protective arms and legs are a part of my cycling kit. SPF 70 is used on the other exposed parts, namely my face and neck. Prevention. It’s never too late, I suppose. It beats the consequences of my youthful naiveté masked as virility. In January of next year, I have my six month follow-up exam. I’m hopeful that I will get the all clear, until the following exam in July.

Despite displaying the battle scars of freedom, I’m not ready to look like the patchwork of grandma’s quilt, but it beats an early departure for the dirt farm to join her…

My advice? If you’ve spent anytime in the sun be aware of the consequences! Also, you’re likely to gain more weight from the donuts than lose weight from the removal of the cancer…