Maps: They’re Really Invitations…

…each one offering new knowledge. Or a route to conquer new lands. Maps get at the fundamental question of “where is this place in relation to everything else I know?” Or answering the question ‘what do I want?’ in the case of kings (actual and would be, wink, wink, nod, nod) and conquistadors seeking new lands to conquer.

My earliest encounter, as I remember, was with the colorful US state map puzzles in elementary school. In figuring out the spatial relations of states borders with their identities, geography was revealed. Classroom globes and Nystrom pull-down maps gave me a sense of the scale of place. It was also around that time when a subscription to the National Geographic magazine introduced maps with their rich colors and cultural details. I also learned that Greenland is not larger than the African Continent once the Mercator Projection illusion was explained.

Then came California State Automobile Association maps that guided my fledgling journeys from the nest as a newly licensed driver.

Around that time, topographic maps of the Sierra became the next oracle at whose feet I spent hours in the off-season exploring potential backpacking adventures for the summer. From learning how to use a compass for navigating crosscountry routes, and as I developed a love of sailing, marine charts taught me to read water the way the backpacker reads terrain and how a compass heading would get me safely from point A to B on land as well as water. A collateral effect to marine maps was to avoid submerged hazards or wayward currents in the Central Coastal waterways of California, since boats with holes in the hull don’t float very well.

There was a time that whenever traveling I went out of my way to find sources of maps whether at gas stations, visitor centers, bookstores, marinas, or any other map wielding enterprises I might encounter, anticipating yet another magically satisfying guide to my curiosity about the world.

60/40 the “Golden Ratio”

Whenever I read about an unfamiliar place or see such a place in a YouTube video, or on television, or come up in conversation, I always seem to open Google Maps to see that place in the context of geography and topography. It’s generally the story in the piece about the place that leads me to look up that particular spot. As I’ve come to expect rapid change in the evolution of technology, Google Earth and Maps, presented a whole new way to satisfy my curiosity of a place. I go to Google first to get the big picture. I’m really trying to read a place, not just locate it. I sort of see a 60/40 split between the context of a place and its location on a map.

Each view in the Google cartography catalog is like a different chapter about a place in context. Satellite view gives us the ground truth—the actual colors and textures, the patterns of development or wilderness, how light or dark it is, whether it’s green or brown or white. We can see things like agricultural patterns, the density of settlement, the relationship between built and natural environments. Terrain view tells us the story that gravity tells—where water flows, what’s difficult to cross, why settlements are where they are, what views people might have. It’s the view that the backpacker and sailor in me probably gravitates toward instinctively, because I’ve learned to read consequences in contour lines. And the Standard view gives us the human overlay—the names, the roads, the political boundaries, the infrastructure. It’s the interpreted landscape, the one that shows us how people have organized and named and connected things that makes up the context.

Using all three together, I’m essentially triangulating—getting a more complete picture than any single view could give me. I’m catching things like: “Oh, this town that sounded random is actually at a mountain pass” or “This coastal city has a natural harbor that explains everything about its history” or “These two places that seem close are actually separated by serious terrain.” It’s almost a form of due diligence before my imagination fully commits to a place. It’s like I need to see it from multiple angles before I really know it. Thanks also to Wikipedia et. al. for providing further context.

Cartographic Curiosity

That reflex to open Google Maps when I encounter a new place name—I think that’s the same cartographic curiosity in my past experiences with maps, just a bit more evolved. I’m not just passively receiving information about a place; I’m actively situating it, understanding its neighbors, seeing how it fits into the larger puzzle, but not as confusing as the four corner states in that elementary puzzle. It’s a form of engagement, really. Different map types have probably shaped different aspects of my curiosity. The topo maps from backpacking taught me to read landscape in three dimensions on a two dimensional plane, to anticipate what’s around the bend. Marine charts taught me about hidden geography—the shapes beneath the surface that matter just as much as what’s visible. Each type of map is almost like learning a different language for understanding a place.

For bicycling and motorcycle adventures, Plotaroute and Rever deliver both planning and real time features of tracking terrain. Interestingly, Butler Motorcycle maps are a throwback to the AAA roadmaps of yesteryear (although AAA roadmaps are still available and updated from their predecessors). Butler maps differentiate between different types of road criteria (road undulation/twisties, elevation change, scenery and peril) in the traditional folding paper maps, albeit in waterproof and tear resistant forms. From the Rever (in collaboration with Butler Maps) website: The recommendations are illustrated on the map by color-coded overlays indicating the quality and/or type of road. Those are illustrated as follows:

As you can see, the Butler/Rever collaboration offers the benefits of using an app in real time on the moto rather than stopping to drag out and unfold a paper map, which in the wind presents challenges of a different sort.

The Butler Paradox

I use Butler Motorcycle maps in planning my “moto-adventures” along with digital and other resources. I’ve written about them in my blog, sisyphusdw7.com using the maps in the context of their rating system of roads as G1, G2, and G3 and my parodying them by rating some blasé road out of Huron, California on which a blind intersection or straight away sight lines obscured by rolling hills and impatient cagers, speed-drunk, make for peril that Butler chooses to define a little differently. From my blog, 2021 Spring Mojave Moto: To See a National Park Devoted to a Tree…:

Pouring over Google satellite views of our intended route was subordinate to the Butler Motorcycle Maps criteria of Lost Highways and PMT’s (Paved Mountain Trails) and G1-3 routes. These byways are also a throwback to the roads I’ve pedalled over in another time and place and that I’m trying to reprise on the moto before riding off into the sunset.

“A Butler Lost Highway [is one] of faded center lines, crumbling shoulders, and long lonely miles putting these roads in a category of their own. These are the roads that seem lost in time. It is what these roads lack that make them worth the journey.”

“A Butler PMT sweeps through the remote forests and mountain ranges of California that are paths of pavement that leave even the most seasoned riders searching for ways to describe their riding experience. These roads are exceptionally tight and twisty and other unique opportunities to explore the less traveled corners of California.”

Those descriptions are from the editors of Butler maps. I’ll add the first of a few more categories of my own, the Jones PARoC‘s (Paved Ag Roads of California), or, “Two lane roads astoundingly arrow straight with right angled intersections bordered by crop obscuring sight lines and stop signs, double yellow line disregarding, pucker inducing, impatient cagers of questionable sobriety trying to pass anything with ≥ 2 or ≤ 18 wheels.”

My parody ratings, PARoC’s (Paved Ag Roads of California) highlight what Butler Maps don’t show—the agricultural hazards, the blind intersections hidden by orchards, the deceptive rolling hills where you can’t see what’s coming over the crest. A perfectly straight farm road could be a G3 in the Butler system but a terror rating in the Sisyphus system if it’s got dust-covered blind corners and ag equipment pulling out unpredictably, which in the agricultural heartland of California, is a year round hazard, as are speed-drunk cagers. These PAROC’s are theG-ratings for anxiety rather than joy. A perfectly straight farm road could be a G3 in the Butler system but a terror rating in the Sisyphus system if it’s got dust-covered blind corners and ag equipment pulling out unpredictably or oncoming cars passing slow moving trucks.

The Paradox Explained

On a recent episode of The Lowdown hosted by Neil Graham The Best Motorcycle Ride in America, Scott Calhoun, a co-founder of Butler Maps, told the origin story of this tool I, like thousands of other riders rely on. I better understand how they decided what made a road a G1 versus a G3, what criteria mattered, how they balanced twistiness with scenery with pavement quality with traffic. Butler Maps are really selling a curated experience, aren’t they? They’re not just showing you how to get somewhere; they’re saying “these are the roads worth riding for their own sake.” The map becomes aspirational—a collection of possible adventures rather than just routes.

While my blog may be a shameless imitation, my integration strategy is straightforward—using Butler roads as the backbone or highlight reels of longer journeys, the sections I’m actually looking forward to rather than just enduring to get somewhere. A G3 road isn’t necessarily “better” than a G1—it’s just different. A newer rider, someone on a heavy touring bike, or someone who just wants a scenic cruise without technical demands might specifically seek out G3s. Meanwhile, the experienced rider on a nimble bike looking for that flow state of linked corners gravitates toward G1s. And G2s are that sweet spot—interesting enough to be engaging, but not demanding your full concentration on every curve. Aristotle would recognize it: the mean between extremes, neither a boring slog nor a white-knuckle terror.

The fact that I’ve chronicled a couple dozen of these multi-day, multi-state rides on my blog suggests I’ve become something of a cartographer myself—documenting not just the routes but the experience of riding them, occasionally noting when Butler’s assessment matched mine, when conditions had changed, and what I discovered that the map couldn’t show.

Into the Unknown

There’s also the aspect of using a map as a security blanket in planning any outing, whether on foot, a bicycle, motorcycle, (BTW, I’ve catalogued dozens of rides on Plotaroute, Rever, and Google Maps with links on my moto blogs), or a sailboat on the bay, basically, any adventure into the unknown. It’s nice to have a preview of what awaits and some degree of preparedness for the inevitable, unknowns. Maps don’t eliminate the unknown, there will always be unknowns, but they shrink them to a manageable size. You can see the big climb coming, know where the water crossings are, anticipate when you’ll be exposed or sheltered. It’s not about controlling everything; it’s about not being blindsided

A dramatic coastline or mountain range can grab you on its own merits. That’s the 40% of a map’s utility I noted earlier. The geography itself poses questions about how it formed, what it’s like to be there, how people navigate it. But that 60% of a map’s utility, context, means the stories attached to places are what really animate them for me. A town becomes more interesting when you know it was the setting of some historical event, or that someone you’re reading about lived there, or that it’s mentioned in a documentary about a particular way of life.

Shrunken to a manageable size

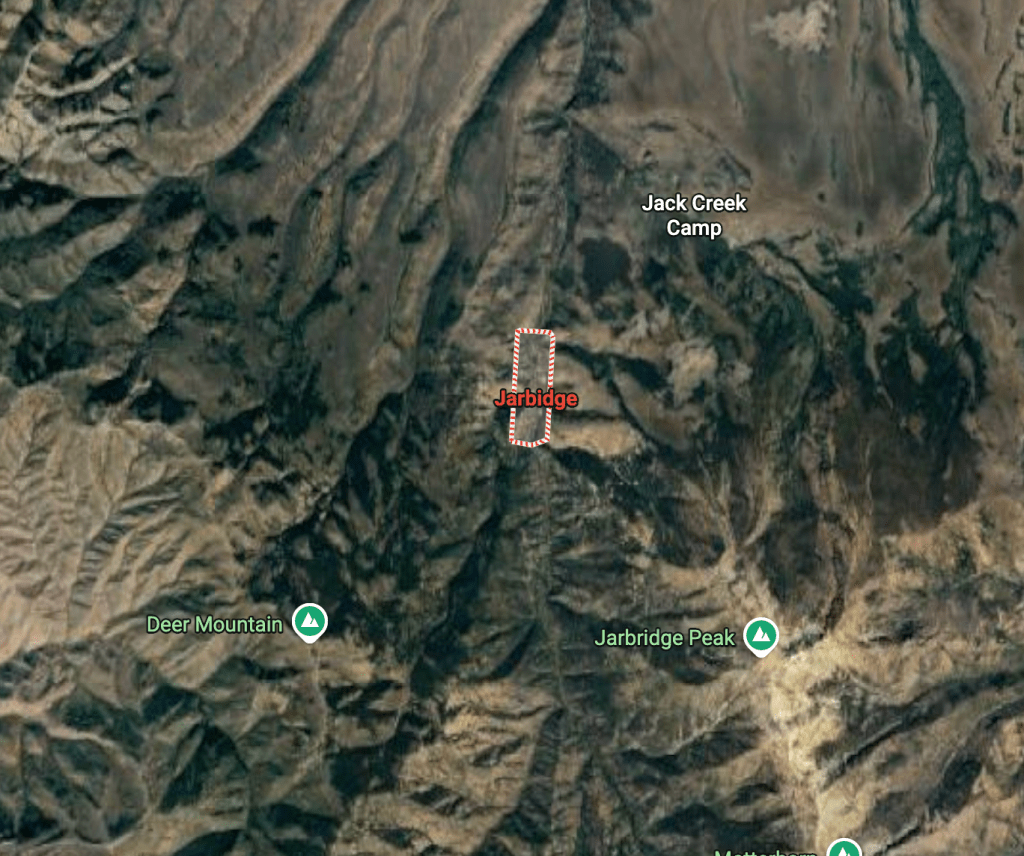

Those two elements probably feed each other, don’t they? The context makes me look at the map, and then the geography adds new dimensions to the story. You hear about a remote town in Nevada, say Jarbidge, and look it up—and suddenly you’re understanding why it’s remote, what kind of journey it would take to get there, and what the surrounding terrain tells you about how people live. The map fills in what the story left out, or sometimes contradicts what you imagined. Just in case you’re curious: Jarbidge, Nevada

By cataloguing many of my rides on my blog, in Plotaroute, Rever, or Google Maps—I’m essentially building my own atlas of personal experience. Each mapped route is a record of a negotiation between what I hoped to find and what I actually encountered. I sometimes look back at those routes and remember specific moments: where we stopped, where it was harder than expected, where we found something surprising.

The “preview” aspect is interesting too. I’m essentially doing reconnaissance from my desk or phone—checking grades, finding bailout points, seeing whether that road actually goes through or dead-ends. The multi-state rides require a different kind of planning too. I’m not just stringing together good roads; I’m thinking about daily mileage, where to stay, weather patterns across regions, the rhythm of challenging sections versus easier cruising. The Butler roads become ingredients in a larger recipe I’m composing. For motorcycle rides especially, knowing what kind of curves are coming, whether the pavement is likely to be good, if there are services along the way—that’s not just convenience, it’s safety.

OMD, (Obsessive Map Disorder)

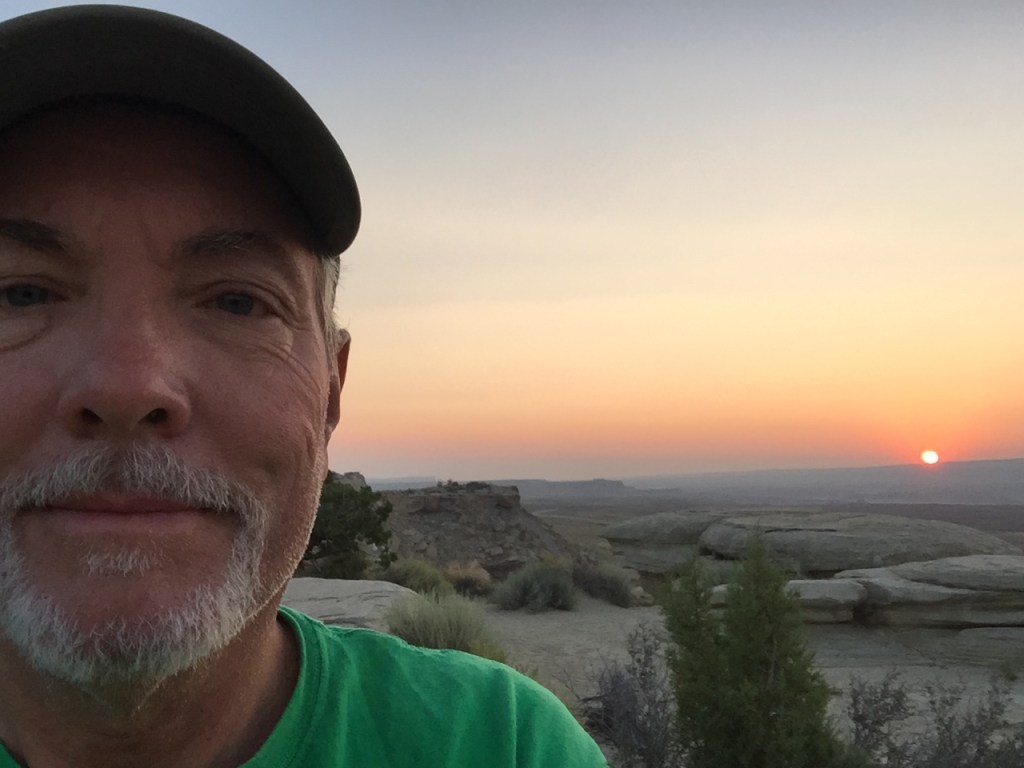

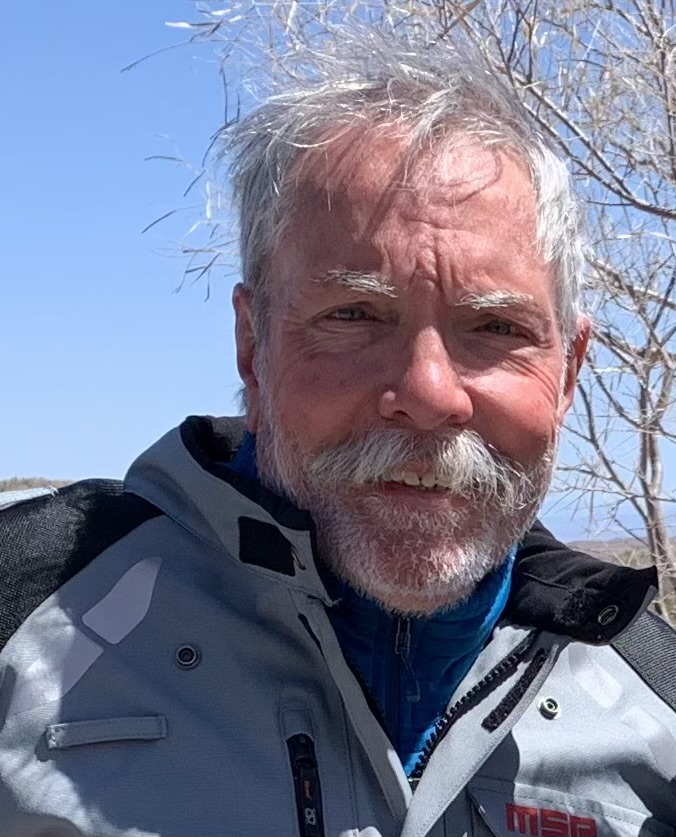

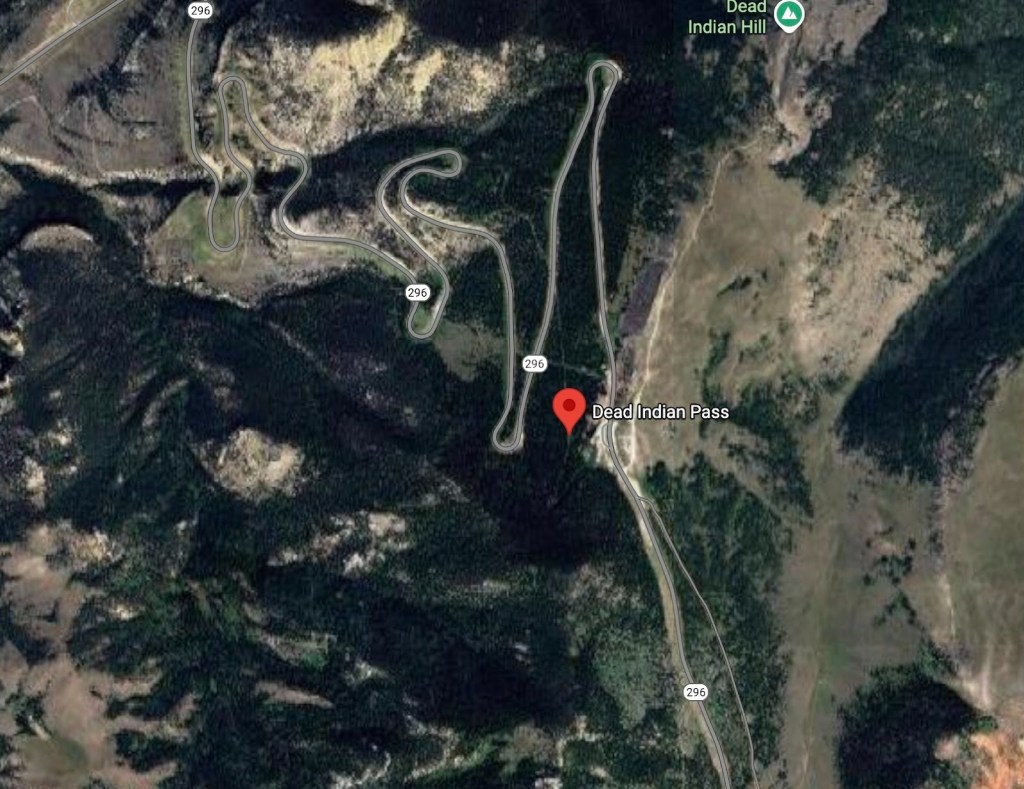

That’s Larry on the right and me on the left on the Chief Joseph Trail, WY-296, at Dead Indian Pass in Wyoming in July, 2002

I cannot complete this “Confession of OMD” without noting the Western States bicycle rides with various groups of knuckleheads that were planned by our dear departed friend, Larry Johnston. It has contributed to the scope of my relationship with maps and trip planning—from those National Geographic maps of childhood to literally crossing entire states under our own power, relying on Larry Johnston’s meticulous planning. Bicycle touring in July—when most people avoid being outside—speaks to a particular kind of commitment. And doing it state by state through the West, we experienced the geography in the most intimate way possible: at bicycle speed, feeling every grade, every wind pattern, every temperature shift. That’s reading the map with your legs and lungs. The planning for those trips was critical—water sources, daily mileage limits, places to resupply, lodging, bailout options if someone struggled. In my tribute to Larry, the friend who did that cartographic labor of love for the group, I hoped to honor the often-invisible work of the planner. Someone has to be thinking three days ahead while everyone else is just focused on the day’s ride.

I hope that my current motorcycle and bicycle itineraries with distances and profiles on Google Map and Plotaroute links embedded on sisyphusdw7.com are carrying forward that same ethic. I’m not just documenting my trips. I’m creating usable maps for others, the way Larry did for us. Each route I share is another invitation, the kind I first accepted when I put together those state puzzles so long ago…

10.31.2025