From 5 to 70 light years, just like that!

How Photos, Their Subjects, and Technology Age

As a Boomer, I recently came across an interesting social media exchange about Steve Martin’s appearance. A Gen-X user had commented on how much Martin has aged compared to his younger days. This struck me as curious, since Martin has famously sported gray hair throughout most of his career. While contemplating this, I noticed a Gen-X FB friend replied that she thought Martin looked virtually unchanged since 1979. The ambiguity of this second comment intrigued me – was it a subtle compliment suggesting his timeless appearance, or a backhanded remark implying he’s always looked older than his years?

The current flood of “then and now” photo comparisons on social media stands in stark contrast to photography’s more deliberate past. I began to consider my photo archive from “then” and those “now.” One consideration was that before 2009’s smartphone revolution, taking a photo was an intentional act requiring some form of dedicated equipment, a modicum of skill, and patience.

In the 1950s, the Kodak Brownie Hawkeye represented the everyman’s camera – a simple box that democratized family photography. The 1960s brought the Kodak Instamatic 110, which made the process more convenient but still required a ritualistic journey: shooting the roll of film, carefully rewinding it, taking it to a photo center, and waiting days for prints to return. Each frame was precious, as you had a limited number per roll and couldn’t preview your results.

The Polaroid camera’s arrival marked a revolutionary shift – the first “instant” photography that produced physical prints within minutes. Its self-developing photos seemed magical at the time, though the image quality often left something to be desired. Still, it offered the first taste of immediate photographic gratification that we now take for granted.

This history makes today’s endless stream of digital photos and instant sharing seem almost surreal in comparison. We’ve moved from carefully rationing 12 or 24 exposures per roll to having virtually unlimited capacity to capture and instantly share every moment. Having social apps that enable downloading photos, whether original or those scrubbed from the internet, then memed, makes for sensory overload at times.

My first camera in 1978, a Pentax MX SLR, represented a serious commitment to photography in an era when “serious” meant investing in manual controls, interchangeable lenses, and 35mm film. The MX, introduced in 1976, was known for its compact size and mechanical reliability – a worthy first venture into serious photography until I discovered the camera, lenses, a tripod, and other necessaries, added significant weight to an already burdensome backpack.

Armed with my “serious” camera, I wasn’t really interested in developing film. While many photography enthusiasts romanticize the darkroom experience, the reality involved handling some notably hazardous chemicals. The process required developers containing hydroquinone and metol, fixers with sodium thiosulfate, and various other chemicals that we now know can pose significant health risks through skin contact and inhalation. The stop baths were essentially acetic acid solutions, and the various toners often contained selenium or other potentially toxic compounds. Contact sheets be damned!

The progression from those days to today’s digital imaging technology has not only democratized photography but also eliminated these chemical hazards from the average photographer’s experience. My Pentax MX represented a fascinating bridge between the simple point-and-shoot cameras of the mass market and today’s digital technology – a time when “serious” photography required not just technical skill but also a willingness to invest in both equipment and process.

I progressed from the manual Pentax MX to the Canon EOS Rebel marking a significant shift toward automated photography, even while still anchored in the film era. The Rebel series represented Canon’s push to make SLR photography more accessible, with its autofocus and automated exposure systems. Costco’s addition of CD digitization with film processing was an interesting technological bridge – one foot in the analog world of film, one in the digital future. Then along came a series of point-and-shoot cameras when a pic was needed in a snap.

The Canon DSLR that eliminated the hybrid workflow, bringing everything into the digital realm. The microSD storage meant no more waiting for processing, no more finite rolls of film, and instant review of results. Yet it made for continuing to carry dedicated photography equipment with interchangeable lenses, a tripod, and the use of manual controls when desired. One needed to continue to develop skills along with an “eye” for subject and composition with no guarantee of a quality photograph.

By 2007 the iPhone revolution, fundamentally transformed photography from a deliberate activity into an almost unconscious one. Gone was the need to:

- Calculate exposure with light meters

- Adjust aperture settings for depth of field

- Choose film speed (ASA/ISO) based on lighting conditions

- Carry an arsenal of specialized lenses, filters, and accessories like a tripod

- Master the technical aspects of photography before getting decent results

The smartphone essentially democratized decent, if not good, photography, turning it from a skilled pursuit into a point-and-shoot affair with computational photography handling all the complex decisions behind the scenes. The best camera truly became the one you had with you – which was now always in your pocket, and for the adventurist, built in editing effects were available to enhance a decent photo into a good photo.

This shift hasn’t just changed how we take photos, but why and what we photograph. The iPhone era has transformed photography from documenting special moments to capturing and sharing every aspect of daily life, for better or worse as witnessed in sisyphusdw7.com.

The following photos represent a perfectly modest snapshot of photography’s great divide – the pre and post-iPhone era. In my collection of in excess of 35,000+ images, roughly 30±% originated from processed film, capturing decades of my life before 2009, while 68±% were born digital from my Canon SLR & DSLR eras. The fact that only 2% of my printed photos, approximately 210, have made the transition to digital format through scanning is a common modern dilemma.

This tiny 2% conversion rate speaks volumes about a challenge many face: thousands of printed photographs sitting in albums, boxes, or envelopes, waiting to bridge the analog-digital divide, especially those of the generation prior to mine. These physical photos represent a kind of trapped history – memories that with time are deteriorating. They can’t be easily shared, backed up, or integrated into our current digital life narratives, unless you consider sitting next to a digital scanner a celebration of freedom from “trapped history”.

The iPhone 3GS purchase in 2009 marks my clear transition point into the era of ubiquitous photography. Unlike the carefully rationed shots of the film era or even the more abundant but still deliberate photos from my SLR and DSLR period, the 3GS ushered in an age where every moment could be casually documented, no development or downloading required, and continues through an iPhone 7 to my current iPhone 12 Pro. It took documenting student tours of Washington, D.C. and the Big Apple, a growing family, and a few adventures pre and post-retirement to familiarize myself with the ubiquitous “better or worse” instant capturing of life.

This technological evolution has created an interesting archival split: pre-2009 memories requiring physical storage and preservation, while post-2009 photos exist primarily as digital files, easily shared but potentially vulnerable to different kinds of loss or degradation.

This collection of images tells an interesting chronological story through different photographic eras and styles.

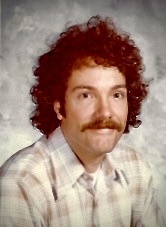

The top row starts with the iconic “What, Me Worry?” Alfred E. Neuman MAD Magazine illustration that sharpened my appreciation of absurd humor. Followed by what is a late 1950s black and white studio portrait of a young Sisyphus in a plaid shirt – taken with the type of formal photography equipment and style common in that era. The third image shows the distinct style in 1979 with longish curly hair and mustache, having that slightly soft focus quality typical of school portrait photography of that period.

The middle row captures the 1980s/early 90s sailing style with vibrant colors (the red Pataguchi fleece by the water, the patterned wedding shirt in the middle shot, and the teal sweatshirt complete with LYSA logo). The photo quality and color saturation indicates they were taken with higher-end film cameras of that era.

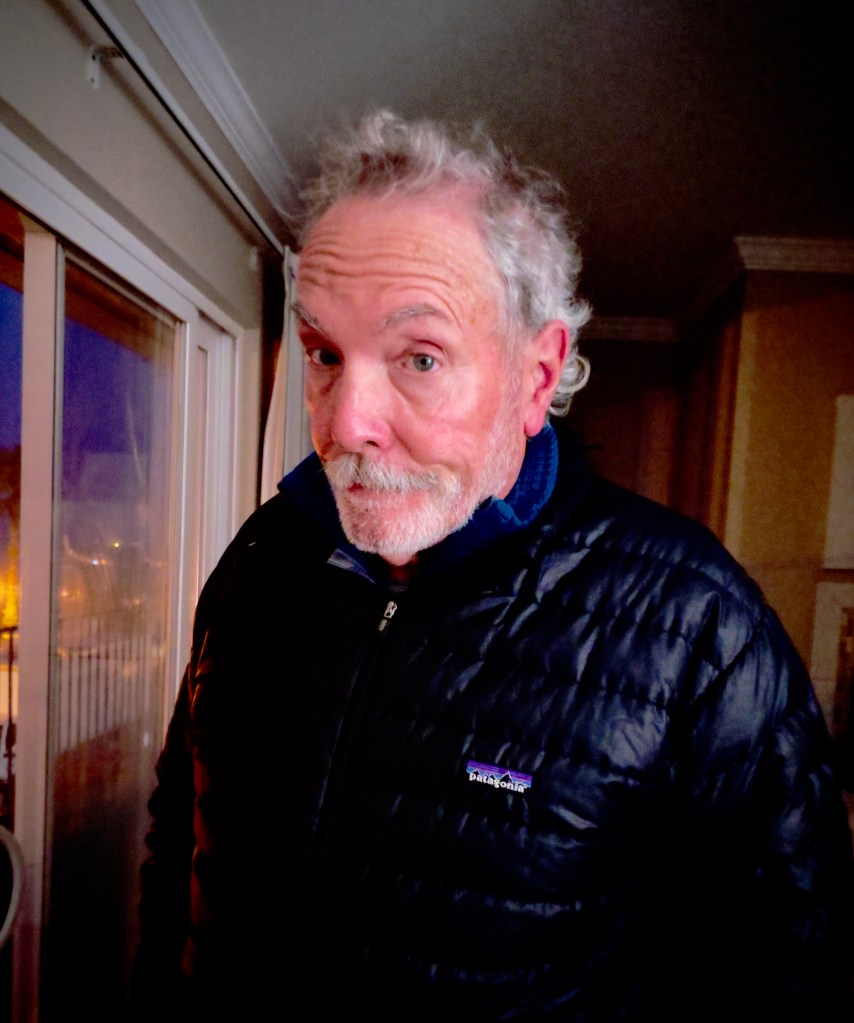

The bottom row shows the progression into the more recent digital era, with increasingly sharp image quality rendered by 35 mm point-and-shoots. The cycling gear shot from a Fuji Discovery Tele, the outdoor backpack photo with the sun hat taken with a Cannon Powershot, and finally what is a recent smartphone-captured image with excellent detail and dynamic range, showing a Sisyphus and the Mrs. in casual outdoor wear.

The second uploaded image pair shows a recent photo in what appears to be a geezer, just sayin’, juxtaposed with “The Dude” meme from The Big Lebowski with its profound message about aging – a fitting bookend to my photographic journey that started with the Alfred E. Neuman’s OG meme. A reminder that I need not obsess about age as long as I keep my foot on the rock and pat my foot, don’t stop, put my foot on the rock…

Mt. Raymond circa 1973

Lydia Pense circa 1973